In Praise of Unrevising

Last week, while searching for something in the innermost bowels of my disastrous email inbox, I discovered about ten different drafts of an essay I was working on five years ago.

I’ve long since forgotten why I felt the need to compulsively mail myself version after version of this essay, but I suspect I was working on a computer that had proven itself untrustworthy.

Curious, I read through these drafts, and to my abject surprise, I discovered that I liked the first draft far, far better than I liked the tenth draft.

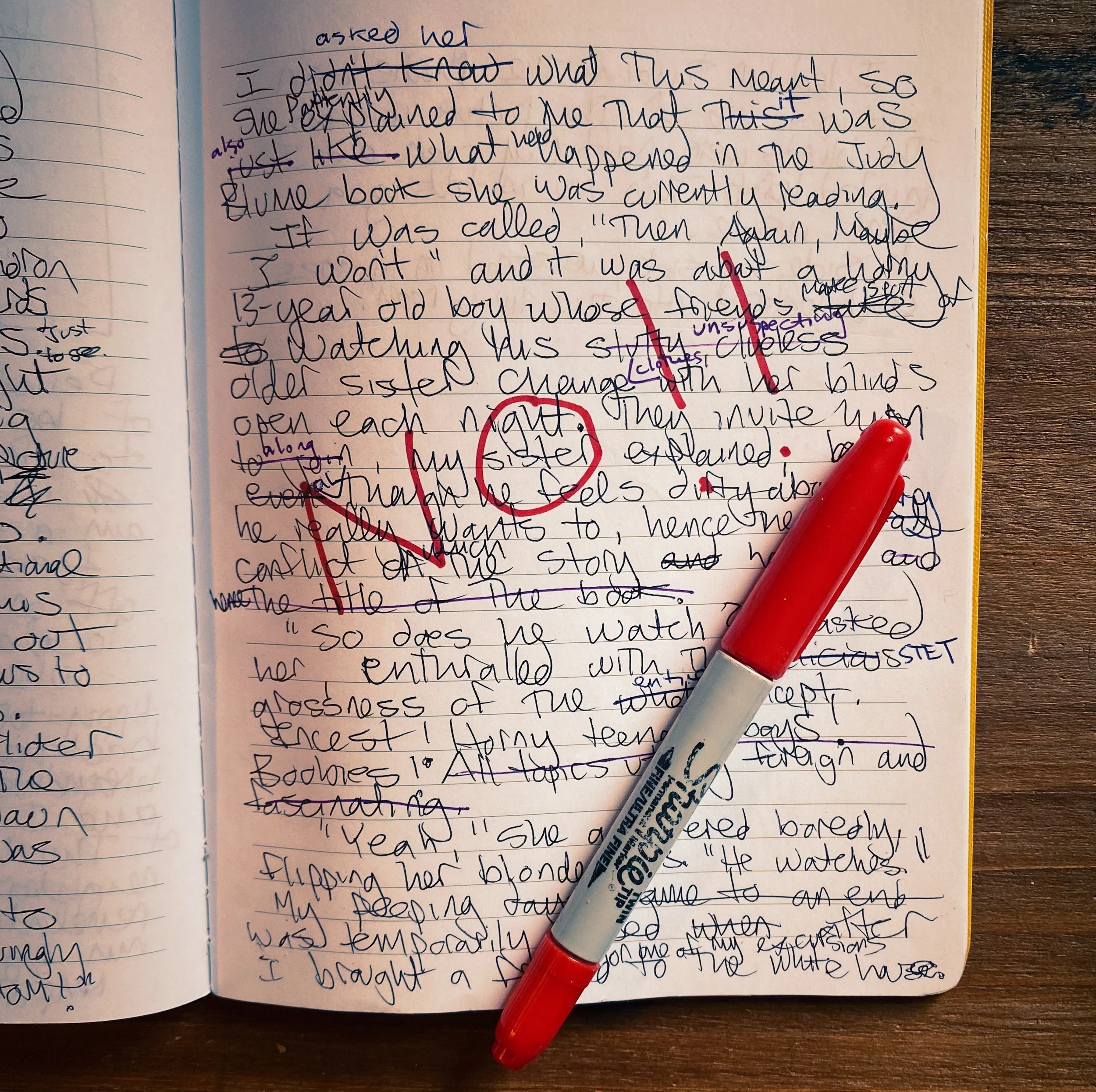

But how could that be, when I labored so long and hard to improve upon those initial drafts? I mean, the proof of my efforts was right there! Revision is synonymous with forward progress, right, or why bother? Nobody revises their work with an eye for deliberately making it worse!

I’ve written before about how first drafts are invariably the most honest ones. There is another argument to be made in favor of holding tightly to the first, second, third, fourth and sixtieth drafts, and revisiting them on the regular, and it is this: Sometimes, they turn out to be straight up superior to your “final draft.”

Sometimes, in your earnest efforts to make a draft better, you’ve managed to make it worse instead.

But whyyyyyy?

I think it’s got to do with the ways we tend to bog down stories with all sorts of parenthetical wisdom and clarifying detail that isn’t actually needed or even particularly interesting.

Sometimes you end up trying to make a story do too much and the result is a saggy, baggy narrative that hobbles along, the essential idea lost amidst your ceaseless attempts to improve and expand upon it.

Why is the first draft so special? Well, often, we are simply jotting down the broad strokes of an idea, and so we have less of an agenda. We aren’t trying to make the writing do or be or prove anything just yet; we’re only spitballing ideas to get them out of our head.

By the tenth draft, on the other hand, we absolutely have an agenda and a goal and a thing we are trying to make our work do. And if we have editors, they might have weighed in as well about what’s theoretically missing.

And sometimes the pressure we impose on our works is far too great, which renders later drafts bloated, overwrought, and bulging out in all the wrong places.

And this bloat isn’t always evident at first glance. Because we are invariably too close to the work to see it unless we’ve stepped away for some period of time.

My suggestions for battling the bulge:

Work with editors who subscribe to the less-is-more mandate whenever you can. Then listen to their advice.

Build in time to walk away from a project and cleanse your creative palate.

Collect parenthetical discoveries you make while working on a piece somewhere, but for God’s sake, don’t collect them within the piece itself. They don’t live there.

And above all, save multiple drafts when you’re working through a piece you care very much about: You might well decide to junk your earnest efforts one or ten or sixty months from now.

It boggles the mind, but I swear it’s true: A bold and radically unsentimental session of unrevising can occasionally turn out to be the wisest kind of revision a writer can make.